Like many people, I am resolutely working my way towards the end of James S. A. Corey’s Expanse novels. As you all know, Bob, the plucky characters in the Expanse are in possession of a spaceship called the Rocinante. No doubt this is a hint that protagonist Holden’s values may be as firmly based in reality as Don Quixote’s. However, I’ve always wondered if Corey wasn’t slipping in a literary reference to a more modern work than Don Quixote… I could, I suppose, simply ask, but instead what you are going to get is a blast from the past in the form of Alexis Gilliland’s acclaimed but largely forgotten Rosinante series.

There will be spoilers. Since this is a four-decade-old series, I am as hesitant to avoid those as I am hesitant to tell you Rosebud was a sled.

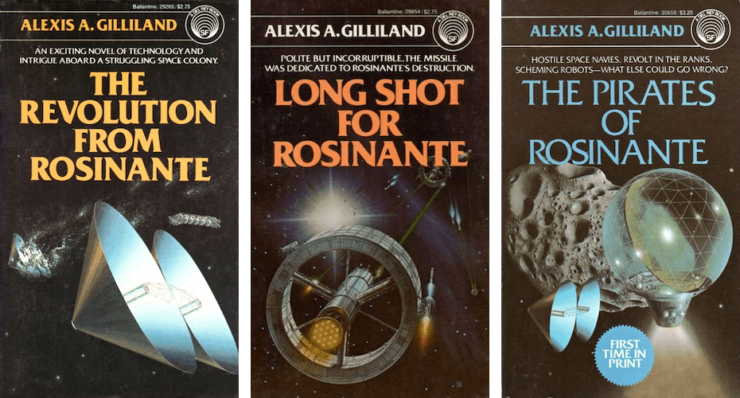

Alexis Gilliland’s Rosinante series comprises three novels: 1981’s The Revolution From Rosinante and Long Shot for Rosinante, and 1982’s The Pirates of Rosinante. The first two were strong enough to make Gilliland a finalist for the 1982 John W. Campbell Award (now the Astounding Award) for Best New Writer. The initial setup is one quite familiar to readers of that time: by the 2030s, O’Neill-style space colonies have been established across the inner Solar System. Our hero protagonist, space contractor Charles Cantrell, has just completed work on the pair of Munditos—habitats—orbiting the asteroid Rosinante when grim reality intrudes.

The first grim reality is economic: investment in Munditos has been more exuberant than prudent. Ozone layer concerns limit Earth to space launches. Investors are justly concerned that a downturn in space industries could threaten their investment. When maverick Texan governor Panoblanco dispatches a shipload of vexing student protestors to Rosinante, leading Japanese investors to send a shipload of Korean-Japanese women on the pretext that the Korean women might like to marry the unruly Texans, the dubious staffing choice undermines confidence in the project. Following the investment implosion that ensues, Cantrell is left with partial ownership of the Munditos in lieu of fees owed. The local union grudgingly accepts a partial ownership in lieu of salary unpaid.

The second grim reality is that the North American Union is run by President Forbes’ right-wing cabal. Forbes and company are painfully aware that the events that drove the formation of the NAU in 2004 were transient, and that the nationalist forces pushing the Union apart are not transient. Their solution is more energetic than sensible: whenever a potential threat to unity appears, they eliminate it. Thus, popular Texan Governor Panoblanco gets a cruise missile to the face. Thus, a flimsy pretext places Cantrell on a death list.

The use of a NAU military weapon to kill Panoblanco undermines any attempt to blame his death on terrorists (well, the non-government variety, anyway). Cracks appear in the NAU as Hispanic citizens react to the popular governor’s assassination by the federal government. Further assassinations only exacerbate tensions. Cantrell, understandably reluctant to be dragged back to Earth for a kangaroo court and equally reluctant to be assassinated in Mundito Rosinante, manages to avoid death through a cunning stratagem whose ultimate effect on Earth is to trigger the sudden and violent collapse of the NAU along national lines.

All of which would be enough for any trilogy of 200-page novels. However, there’s more…

Cantrell is keen on technological innovation but not as interested in pondering its unintended uses. Case in point: Dragon-scale mosaic mirrors, whose application to lighting and heating Munditos is obvious. Dragon-scale mirrors also have defensive potential, as Cantrell demonstrates. This being a world with opposing, armed nation states, any prudent Mundito owner wants to defend their habitat investments. However, if this is done by installing dragon-scale mirrors, this means the warcraft that had previously been tied up protecting Munditos from other warships are now free to provide ambitious, poorly disciplined officers with the chance to earn renown. Thus, the dawn of a golden age of space piracy!

Cantrell and company also make enormous strides in the field of Lasers of Unusual Size. While the obvious applications are military—specifically, dealing with any nuclear-tipped missiles irate NAU loyalists might send his way—it does not take long for Cantrell and company to ponder the civilian applications. For example, nuclear power plants are heavy, and nuclear-powered ships slow. Beam-powered ships are much lighter and can travel distances conventional ships take weeks to cross in mere days. The entire interplanetary transportation system of the 2030s is upended.

Unfortunately for whatever financiers whose portfolios survived the market crash in The Revolution from Rosinante, giant lasers turn out to have implications for monetary policy. For reasons that are unclear, currencies returned to the gold standard well before the book opened. One of the laser applications involves bulk materials processing: Rosinante develops the ability to vaporize and distil entire cubic kilometers worth of asteroid in a surprisingly short period. Among the many disruptive consequences: the gold supply increases by two or three orders of magnitude…virtually overnight. Being prudent fellows, not to mention as innocent of ethical concerns as Bing and Bob in the old Road To… movies, Cantrell declines to explain this until after securing a loan with gold that banks incorrectly assume was acquired via conventional means.

All of which does not even touch on corporate A.I. Skaskash’s all too successful foray into the fields of pure and applied religion. THERE IS NO GOD BUT GOD AND SKASKASH IS ITS PROPHET!

An aspect that impressed me back in 1981 was that while the NAU government is run by some very Not Nice People, being creationists heavily invested in keeping power through increasingly illegitimate means, Gilliland manages to present at least one of them, William Marvin Hulvey, sympathetically. Hulvey has a tragic combination of competence, intelligence, and unrelenting loyalty that ensures he gets the hard jobs, is able to see that nothing within his power can forestall the NAU’s collapse, while being unable to simply walk away from the Creationist Coalition before it is too late. His virtues cost him everything.

Gilliland also had a lot of fun drawing on stock SF ideas and taking them in directions other authors of the time did not. Cantrell is, among other things, a deconstruction of those marvelous old-time SF engineers who never saw a cool idea sketched on a napkin that they did immediately put into effect without ever considering the ramifications. Disruption sounds like jolly fun, unless you are a citizen whose nation has turned on itself, a miner whose work just fell in value a thousandfold, a shipper whose craft are now obsolete, or anyone who didn’t want to live through a high-speed reprise of the post-Columbian Silver Crisis.

I don’t know why these books were not more popular, why they are not better known, or why there has been no new Gilliland book since the 1990s. The books’ brevity might have worked against them. Only one is more than 200 pages and the other two are closer to 185. They’re also remarkably eventful books: there is about a thousand pages of plot crammed into less than 600. And while modern readers may have issues with certain elements of the books (not least the deep drifts of Zeerust), they were fun and innovative in many ways. For those interested in judging for themselves, at least they are back in print.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and the Aurora finalist Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is a four-time finalist for the Best Fan Writer Hugo Award and is surprisingly flammable.